In the mid-1970s, my first wife Mary Jo and I were living in a one-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn, scraping by on my pay as a graduate assistant at Brooklyn College, along with occasional playing gigs for both of us, and her intermittent work at banks and investment companies through temp agencies such as Manpower or Kelly Girl. (Take a moment to contemplate those gendered business names!)

In the mid-1970s, my first wife Mary Jo and I were living in a one-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn, scraping by on my pay as a graduate assistant at Brooklyn College, along with occasional playing gigs for both of us, and her intermittent work at banks and investment companies through temp agencies such as Manpower or Kelly Girl. (Take a moment to contemplate those gendered business names!)

I had heard about this guy in the city, Arnold Arnstein, who hired people to copy music, and thought I should check it out as a way to supplement our income. His office was at 2067 Broadway, a somewhat dingy building just down the block from the Seventy-second Street IRT stop (a building still standing: see photo). You walked up a flight of stairs, drawn to his suite of two or three rooms by the strong reek of ammonia. He was approaching eighty at that point, not very tall, always wearing a jacket and tie, with a thick moustache and unruly white hair, papery skin, and the eyes of someone who spent his days squinting at tiny ink marks. He’d been in the business for years, was Menotti’s principal copyist, had also done lots of music preparation for Broadway shows, film scores, and concert music, including working with some of the leading composers and conductors of the time, such as Bernstein, Blitzstein, Reiner, Mitropoulos, Stravinsky, even Mingus.

I showed him some examples of my copying. He could see I had potential. As a kind of audition, he handed me a printout of the full score of one of their current projects and told me to take it home and copy out three pages of the first oboe part. I came back with it a couple days later. While he seemed satisfied with the part’s basic legibility, he also pointed out several unacceptable flaws, most likely having to do with missing cues or poor page turns. “Go home and do it again,” he said. I did so. It took at least one or two more of these sessions before he decided I was ready. From here on out, I would get paid for my work.

I showed him some examples of my copying. He could see I had potential. As a kind of audition, he handed me a printout of the full score of one of their current projects and told me to take it home and copy out three pages of the first oboe part. I came back with it a couple days later. While he seemed satisfied with the part’s basic legibility, he also pointed out several unacceptable flaws, most likely having to do with missing cues or poor page turns. “Go home and do it again,” he said. I did so. It took at least one or two more of these sessions before he decided I was ready. From here on out, I would get paid for my work.

There were plenty of young copyists working for him, likely including some of the graduates of his music copying course at Juilliard. Some would do their work right there in the office. Many, like me, would take it home. The normal procedure was to have enough scores printed so the work could be divvied up. For one job, I might do the first and second violins while someone else did the lower strings, another did the woodwinds, and so on.

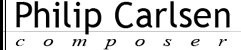

Everything then was written out in ink on semi-transparent onionskin paper on which staff lines had been printed. I used a Rapidograph-type pen and Higgins Black Magic ink, a good friend of left-handers like myself because it dries so quickly. I kept a six-inch, transparent plastic ruler in my right hand for beams, stems, barlines, etc. I also invested in a Bruning electric eraser. I did my lettering free-hand, but many copyists (including Arnie) used a Leroy lettering guide for titles, tempo markings, numbers, and other text. You can see an example of it in this excerpt from Carter’s Concerto for Orchestra:

Everything then was written out in ink on semi-transparent onionskin paper on which staff lines had been printed. I used a Rapidograph-type pen and Higgins Black Magic ink, a good friend of left-handers like myself because it dries so quickly. I kept a six-inch, transparent plastic ruler in my right hand for beams, stems, barlines, etc. I also invested in a Bruning electric eraser. I did my lettering free-hand, but many copyists (including Arnie) used a Leroy lettering guide for titles, tempo markings, numbers, and other text. You can see an example of it in this excerpt from Carter’s Concerto for Orchestra:

Instrument names and time signatures and the circled numbers were obviously made with the Leroy, but nearly everything else is done by hand, with the aid of not much more than a straight edge, a T-square, and perhaps some templates for the slurs. Look closely at the subtle differences between dynamic markings and accidentals and rests—a clear indication that a highly skilled calligrapher was at work here, the mark of the human hand on the page. A beautiful score (of a remarkable piece of music).

For printing, the ink masters were laid on sheets of light yellow, photosensitive paper, and fed as a sandwich into the bright light of the Ozalid machine. This exposed sheet was immediately sent through a different part of the machine that processed it with ammonia vapor, permanently turning the yellow notes and staves and other markings into black or blue. (Here’s a short video showing the process at work.) The machine was the same kind used for architectural blueprints, so it could handle very big sheets of paper—extremely useful for large-format opera and orchestral scores, and for printing in folios, four pages of music on both sides of a single sheet which would be folded in half, and could then be combined with folios of the other pages and bound together with a saddle stapler. The process was quick and efficient and highly flexible, back in the days before computers. Often, you would print a multipage part on just one side of a long roll of photopaper, then fold it up like an accordion when it came out of the machine. That could be dangerous in performance, though. I remember one concert where the solo percussionist reached up to turn a page and the entire score unfolded itself onto the floor like a slinky.

Arnstein urged that we copyists try putting ourselves into the minds of the musicians who would be reading from our parts. Would the player have enough time to turn the page? Were there adequate cues of what was happening in other parts so there would be no question about where to come in after a long rest? Could the player keep track of how many times to repeat a bar? Above all, was the part free of mistakes: wrong notes, missing dynamic markings, incomplete measures? Arnie cherished his reputation in the business for accuracy. Everything was proofread at least twice, ideally three times by three different people. Even before checking for the accuracy of the actual notes, he had us do a “bar-count” of each individual part, using a cheat sheet derived from the score that was laid out as a simple time line, listing the numbers of bars between rehearsal numbers and all markings for tempo. It would quickly show you, for example, if there were only nineteen bars between rehearsal letters B and C when there were supposed to be twenty, a thing easy to miss if there are multiple bars of rests involved and you’re focused primarily on proofreading the notes.

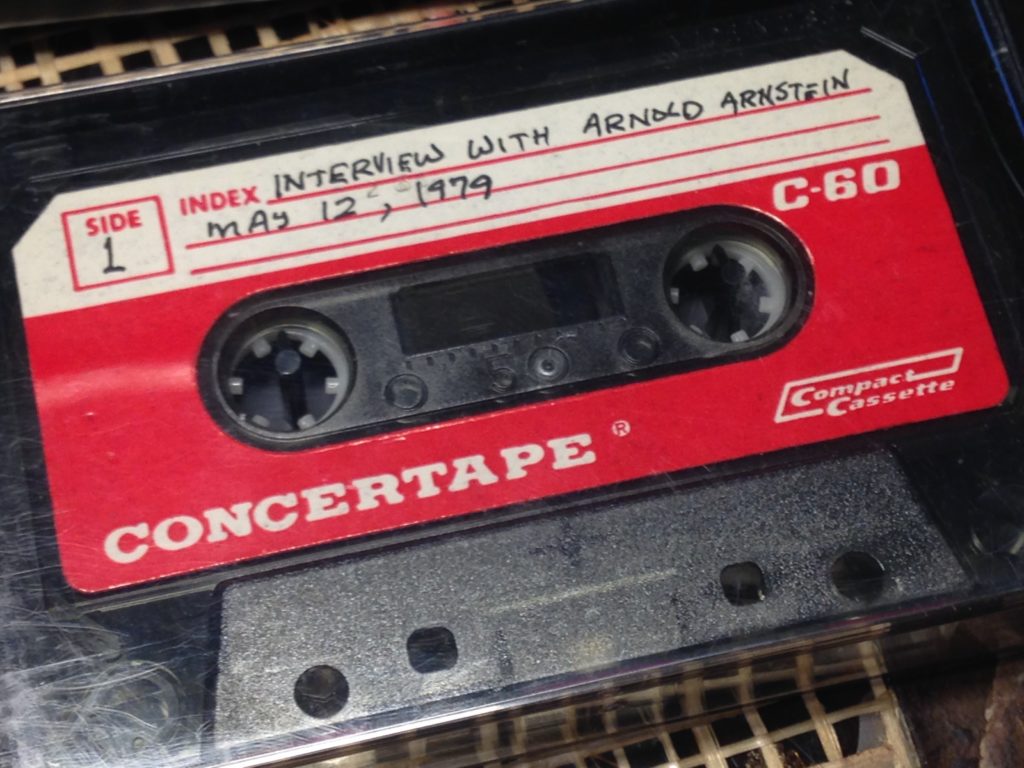

One of my graduate courses at CUNY was “The Sociology of Music,” taught jointly by Barry Brook and Bernard Rosenberg. For my class project, since one of our topics had been oral history, I decided to do a series of interviews with my copying boss, taking a cassette recorder with me up to his office, then sitting down later to transcribe it. In the process of writing this memoir, I thought of those old cassettes again and went looking for them among the boxes I’ve dragged from place to place through my various moves over the years. My original transcription is likely long gone, but fortunately, the cassettes turned up. How remarkable and touching it is to hear Arnie’s voice again. In a future blog, I’ll offer some transcriptions of his reminiscences. Stay tuned.

One of my graduate courses at CUNY was “The Sociology of Music,” taught jointly by Barry Brook and Bernard Rosenberg. For my class project, since one of our topics had been oral history, I decided to do a series of interviews with my copying boss, taking a cassette recorder with me up to his office, then sitting down later to transcribe it. In the process of writing this memoir, I thought of those old cassettes again and went looking for them among the boxes I’ve dragged from place to place through my various moves over the years. My original transcription is likely long gone, but fortunately, the cassettes turned up. How remarkable and touching it is to hear Arnie’s voice again. In a future blog, I’ll offer some transcriptions of his reminiscences. Stay tuned.